Sher Shah Suri

| Sher Shah suri | |

|---|---|

| Emperor of Suri Empire | |

|

|

| Reign | 1540–1545 |

| Coronation | 1540 |

| Born | 1486 |

| Birthplace | Sasaram, India |

| Died | May 22, 1545 |

| Place of death | Kalinjar, India |

| Buried | Sher Shah Suri Tomb, Sasaram, India |

| Predecessor | Humayun |

| Successor | Islam Shah Suri |

| Royal House | Suri Dynasty |

| Father | Hassan Khan Sur |

| Religious beliefs | Sunni Islam |

Sher Shah Suri (1486 - May 22, 1545) (Pashto: شیر شاہ سوری - Šīr Šāh Sūrī), birth name Farid Khan, also known as Sher Khan (The Lion King), was a brave and powerful Afghan (Pashtun)[1][2][3][4][5][6][7] who conquered the Delhi Sultanate in northern India. He served as a private before rising to become a commander in the Mughal army under Babur and then as the governor of Bihar. In 1537, when the new Mughal leader Humayun was elsewhere on an expedition, Sher Shah Suri overran Bengal and became the new emperor after establishing the Suri Empire.[8]

A brilliant strategist, Sher Shah proved himself a gifted administrator as well as an able general. His reorganization of the empire laid the foundations for the later Mughal emperors, notably Akbar, son of Humayun.[8] During his five year rule from 1540 to 1545, he set up a new template for civic and military administration, issued the first Rupee and re-organised the postal system of India.[9] He further developed Humayun's Dina-panah city and named it Shergarh and revived the historical city of Patna which had been in decline since the 7th century CE.[10] He is also famously remembered for killing a fully-grown tiger with his bare hands in the Indian jungle.[1][8]

Contents |

Early life and origin

Sher Khan was born in Sasaram, Bihar, India.[11] His original birth name was Farid-ud-din Abul Muzaffar but mostly called by the simple name as Farid Khan.[1] One of eight or 10 (in some sources it is claimed also of 12) sons of Hassan Khan Sur, a vassal of Sasaram and a horse breeder, Farid rebelled against his father and left home to enlist as a soldier in the service of Jamal Khan, the governor of Jaunpur (Uttar Pradesh). He later became known as Sher Khan after he killed a full-sized tiger (sher) with his bare hands. Particularly for this event and generally for his ferocity as a warrior, he was then, later on, called Sultan-E-Azam Sher Shah Suri meaning the great lion emperor Sher Shah Suri.[1][8]

Sher Khan belonged to the Sur ethnic Pashtun tribe (known as Afghan in historical Persian language sources).[12] His parents were Afghan nobility who descended from a nobleman adventurer (Ibrahim Khan Sur) recruited much earlier by Sultan Bahlul Lodi of Delhi during his long contest with the Sharqi Sultans of Jaunpur. Most commonly amongst the Pashtuns (Pathans) warrior tribes of the Indian Subcontinent, he is regarded as one of the most fierce and great emperors of Asia.

It was at the time of this bounty of Sultán Bahlol, that the grandfather of Sher Sháh, by name Ibráhím Khán Súr,*[The Súr represent themselves as descendants of Muhammad Súr, one of the princes of the house of the Ghorian, who left his native country, and married a daughter of one of the Afghán chiefs of Roh.] with his son Hasan Khán, the father of Sher Sháh, came to Hindu-stán from Afghánistán, from a place which is called in the Afghán tongue “Shargarí,”* but in the Multán tongue “Rohrí.” It is a ridge, a spur of the Sulaimán Mountains, about six or seven kos in length, situated on the banks of the Gumal. They entered into the service of Muhabbat Khán Súr, Dáúd Sáhú-khail, to whom Sultán Bahlol had given in jágír the parganas of Hariána and Bahkála, etc., in the Panjáb, and they settled in the pargana of Bajwára.[13]—Ferishta, 1560-1620

Government and administration

Sher Shah became a commander by Babur after serving previously as a private in the Mughal army. After becoming the governor of Bihar, he began reorganizing the administration efficiently. He organised a well disciplined, one of the largest and most efficient army. He also introduced tax collection system, built roads along with resting areas for travellers, dug wells, improved the jurisdiction, founded hospitals, established free kitchens, organized mail services and the police. His management proved so efficiebt that even one of the greatest rulers of human history, the Mughal Emperor Akbar, organised the Indian subcontinent on his measures, and the system which lasted untll the 20th century.

He is also credited for rebuilding the longest highway of the Indian subcontinent in Asia. The highway which is called the "Grand Trunk Road" or the Shahar Rah-e-Azam survives til this day. It is in use in present-day Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Punjab region Punjab, Delhi, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Bengal.

Sher Shah was a visionary ruler and introduced many military and civil reforms. The system of tri-metalism which came to characterise Mughal coinage was largely the creation of Sher Shah Suri. He also minted a coin of silver which was termed the Rupiya that weighed 178 grains and was the precursor of the modern rupee.[9] The same name is still used for the national currency in Pakistan, India, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Indonesia, Mauritius, Maldives, Seychelles among other countries. Gold coins called the Mohur weighing 169 grains and copper coins called Dam were also minted by his government.[9][14]

Mirza Aziz Koka, son of Ataga Khan, and probably Akbar's closest friend and one of the most important mansabdar's of the Mughal Empire, wrote this to Emperor Jahangir in one of his personal letters to him:

"Specially Sher Khan was not an angel (malak) but a king (malik). In six years he gave such stability to the structure (of the empire) that its foundations still survive. He had made India flourish in such a way that the king of Persia and Turan appreciate it, and have a desire to look at it. Hazrat Arsh Ashiyani (Akbar the great) followed his administrative manual (zawabit) for fifty years and did not discontinue them. In the same India due to able administration of the well wishers of the court, nothing is left except rabble and jungles..."

Death and succession

Sher Shah Suri died from a gunpowder explosion during the siege of Kalinjar fort on May 22, 1545 fighting against the Chandel Rajputs. Sher was also the last and the main personality of India to offer serious resistance to the Mughals on their advance to the south, and his death during the siege of Kalinjar (Bundelkhand) in 1545, cleared the path to the return of Mughal emperor Humayun.

Sher Shah Suri was succeeded by his son, Jalal Khan who took the title of Islam Shah Suri, and his imposing and proud mausoleum, the Sher Shah Suri Tomb (122 ft high) stands in the middle of an artificial lake at Sasaram, a town that stands on the Grand Trunk Road, his lasting legacy.[15] His death has also been claimed to have been caused by a fire in his store room.

Tarikh-i-Sher Shahi (History of Sher Shah), written by Abbas Khan Sarwani, a waqia-navis under later Mughal Emperor, Akbar around 1580, provides a detailed documentation about Sher Shah's administration.

Legacy

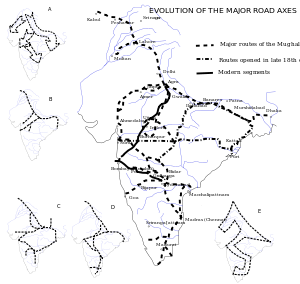

Recent research indicates that during the time of the Maurya empire in the 3rd century BC, overland trade between India and several parts of western Asia and the Hellenic world went through the cities of the north-west, primarily Taxila (located in present day Pakistan)(see inset in map). Taxila was well connected by roads with other parts of the Maurya empire. The Mauryas had built a highway from Taxila to Pataliputra (present-day Patna in Bihar, India). Great Chandragupta Maurya had a whole army of officials overseeing the maintenance of this road as told by the Greek diplomat Megasthenes who spent fifteen years at the Mauryan court.

In the 16th century, a major road running across the Gangetic plain was built afresh by Pashtun emperor Sher Shah Suri, who then ruled much of northern India. His intention was to link together the remote provinces of his vast empire for administrative and military reasons. The Sadak-e-Azam ("great road") as it was then known, is universally recognized as having been the precursor of the Grand Trunk Road.

The road was initially built by Sher Shah to connect Agra, his capital, with Sasaram, his hometown. It was soon extended westward to Multan and eastward to Sonargaon in Bengal (now in Bangladesh). While Sher Shah died after a brief reign, and his dynasty ended soon afterwards, the road endured as his outstanding legacy. The Mughals, who succeeded the Suris, extended the road westwards: at one time, it extended to Kabul in Afghanistan, crossing the Khyber Pass. This road was later improved by the British rulers of colonial India. Renamed the "Grand Trunk Road" (sometimes referred to as the "Long Walk"), it was extended to run from Calcutta to Peshawar and thus to span a major portion of India.

Over the centuries, the road, which was one of the most important trade routes in the region, facilitated both travel and postal communication. Even during the era of Sher Shah Suri, the road was dotted with caravansarais (highway inns) at regular intervals, and trees were planted on both sides of the road to give shade to the passers-by. The road was well planned, with milestones along the whole stretch. Some of these milestones can still be seen along the present Delhi-Ambala highway. On another note, the road also facilitated the rapid movement of troops and of foreign invaders. It expedited the looting raids, into India's interior regions, of Afghan and Persian invaders and also facilitated the movement of British troops from Bengal into the north Indian plain.

The Grand Trunk Road continues to be one of the major arteries of India and Pakistan. The Indian section is part of the ambitious Golden Quadrilateral project. For over four centuries, the Grand Trunk Road has remained "such a river of life as nowhere else exists in the world".[16]

Architectural legacy

Apart from rebuilding the Grand Trunk Road also known as Shahar Rah-e-Azam ("great road"), which stretches across the breadth of Indian subcontinent from Sonargaon in Bangaldesh to Peshwar in Pakistan, he built monuments, many of which no longer exist today, including Rohtas Fort, now a UNESCO World Heritage Site in Pakistan, many structures in the Rohtasgarh Fort in Bihar, Sher Shah Suri Masjid, in Patna, built in 1540-1545 to commemorate his reign.

Qila-i-Kuhna mosque, built by Sher Shah in 1541, at Purana Qila, Delhi, a Humayun citadel started in 1533, and later extended by him, along with the construction of Sher Mandal, an octagonal building inside the Purana Qila, Delhi complex, which later served as the library of Humayun.

Presently a part of Comilla's Court Road, the photographed street had once been an extension of Grand Trunk Road, to communicate with the port facilities of Chittagong |

Lal Darwaza or Sher Shah Gate, the Southern Gate to the Sher Shah Suri's city, Shergarh, opposite Purana Qila, Delhi, also showing with the adjoining curon walls and bastions |

Rohtas Fort's magnificent Kabuli Gate |

Qila-i-Kuhna mosque, built by Sher Shah in 1541, Purana Qila, Delhi |

Sher Mandal built by Sher Shah, Purana Qila, Delhi |

Shersabadia community

Some soldiers were left behind by Sher Shah Suri as he escaped from Bengal, avoiding the Humayun invasion. These people are known as Shersabadia. They made a colony named Shershahabad which is no more due course change of Ganges. Today the people of this community are found in parts of Malda, Murshidabad, Chapai Nawabganj and a few other parts of Bengal

Karachi

Sher Shah neighbourhood and Sher Shah Bridge in Kiamari Town of Karachi, Sindh, Pakistan are named in the honour of Sultan Sher Shah Suri.

Additional reading

- Tarikh-e-Afghani

- Tarikh-i-Sher Shahi

- Tarikh-i Shahi

- Tarikh-i Khan Jahani wa Makhzan-i Afghani

- Edward Thomas (1871) The Chronicles of the Pathan Kings of Delhi

- Kalkar Nijan, Sher Shah And His Times

- Sir Olaf Caroe, The Pathans

- Syed Bahadur Shah Zafar Kakakhel, Pashtoon

See also

- Shere Khan

- Pathan of Bihar

- Delhi Sultanate

- List of rulers of Bengal

- History of Bengal

- History of Bangladesh

- History of India

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 "Shēr Shah of Sūr". Encyclopædia Britannica. 2010. http://www.britannica.com/eb/article-9067304/Sher-Shah-of-Sur. Retrieved 2010-08-23.

- ↑ Chaurasia, Radhey Shyam (2002). History of medieval India: from 1000 A.D. to 1707 A.D. Crabtree Publishing Company. p. 179. ISBN 8126901233, 9788126901234. http://books.google.com/books?id=8XnaL7zPXPUC&source=gbs_navlinks_s. Retrieved 2010-08-23.

- ↑ Mahmud, Sayyid Fayyaz (1963). The Story of Indo-Pakistan. Oxford University Press. p. 135. http://books.google.com/books?id=fcg9AAAAMAAJ&source=gbs_navlinks_s. Retrieved 2010-08-23.

- ↑ Schimmel, Annemarie; Burzine K. Waghmar (2004). The empire of the great Mughals: history, art and culture. Reaktion Books. p. 28. ISBN 1861891857, 9781861891853. http://books.google.com/books?id=N7sewQQzOHUC&source=gbs_navlinks_s. Retrieved 2010-08-23.

- ↑ Singh, Sarina; Lindsay Brown; Paul Clammer; Rodney Cocks; John Mock (2008). Pakistan & the Karakoram Highway. 7, illustrated. Lonely Planet. p. 199. ISBN 1741045428, 9781741045420. http://books.google.com/books?id=zn8I4qEew9oC&source=gbs_navlinks_s. Retrieved 2010-08-23.

- ↑ Greenberger, Robert (2003). A Historical Atlas of Pakistan. The Rosen Publishing Group. p. 28. ISBN 0823938662, 9780823938667. http://books.google.com/books?id=RukebrLEpi4C&source=gbs_navlinks_s. Retrieved 2010-08-23.

- ↑ Levinson, David; Karen Christensen (2002). Enclopedia of Modern Asia: a berkshire reference work. Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 94. ISBN 0684806177, 9780684806174. http://books.google.com/books?id=_qwUAQAAIAAJ&source=gbs_navlinks_s. Retrieved 2010-08-23.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 "Sher Khan". Columbia Encyclopedia. 2010. http://www.infoplease.com/ce6/people/A0844870.html. Retrieved 2010-08-24.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 "Mughal Coinage". Reserve Bank of India RBI Monetary Museum. http://www.rbi.org.in/currency/museum/c-mogul.html. Retrieved 2010-08-24.

- ↑ Patna encyclopedia.com.

- ↑ Sher Shah Suri

- ↑ Weiner, Myron; Ali Banuazizi (1994). The Politics of social transformation in Afghanistan, Iran, and Pakistan. Syracuse University Press. pp. 488. ISBN 0815626088, 9780815626084. http://books.google.com/books?id=TmMJnaMVN6oC&source=gbs_navlinks_s. Retrieved 2006-06-07.

- ↑ Muhammad Qasim Hindu Shah. "CHAPTER I. Account of the reign of Sher Sháh Súr.". Packard Humanities Institute. http://persian.packhum.org/persian/main?url=pf%3Ffile%3D80201016%26ct%3D199%26rqs%3D39%26rqs%3D61%26rqs%3D217%26rqs%3D222%26rqs%3D235%26rqs%3D237%26rqs%3D286%26rqs%3D305%26rqs%3D321%26rqs%3D339%26rqs%3D400%26rqs%3D436%26rqs%3D455. Retrieved 2010-08-23.

- ↑ Rupee

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (Eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press..

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (Eleventh ed.). Cambridge University Press.. - ↑ Catherine B. Asher (1977). "The mausoleum of Sher Shah Suri". Artibus Asiae (Artibus Asiae Publishers) 39 (3/4): 273–298. doi:10.2307/3250169. http://www.jstor.org/pss/3250169.

- ↑ A description of the road by Kipling, found both in his letters and in the novel "Kim". He writes: "Look! Brahmins and chumars, bankers and tinkers, barbers and bunnias, pilgrims -and potters - all the world going and coming. It is to me as a river from which I am withdrawn like a log after a flood. And truly the Grand Trunk Road is a wonderful spectacle. It runs straight, bearing without crowding India's traffic for fifteen hundred miles - such a river of life as nowhere else exists in the world."

External links

- Encyclopedia Britannica - Sher Shah of Sur

- Encyclopedia Britannica - Sur Dynasty

- Columbia Encyclopedia - Sher Khan

- Sher Shah Suri - The Lion King

- Sher Shah brief biography as ruler

| Preceded by - |

Shah of Suri Empire 1539-1545 |

Succeeded by Islam Shah Suri |

|

|||||||||||||||||||